Eleven days ago, as I watched the Detroit Tigers throw away game six of the ALCS, and with it the American League pennant which once they flew, I couldn’t help but reflect on the strange irony of the Tigers’ success. So much had been made of the “return” of Detroit, of its startling comeback from desolation. From Chrysler 300 ads to NBC nightly news talking about how Detroiters are getting used to success (read: Lions and Tigers winning) the city, pundits claimed, was crawling up off the mat.

That should make me happy. But it doesn’t. It makes me confused and melancholy.

Once again I’m reminded of my Dad, a man who welcomed moral confusion into his life like an old drinking buddy. Perhaps because tomorrow would have been his 67th birthday, perhaps because Halloween was his favorite holiday, or perhaps because the Occupy Wall Street protests are in full swing and I know damn well if there wasn’t an Occupy Wall Street Raleigh, he’d have made one (though probably not before taking a bus to Gotham to raise his fist on Wall Street) but whatever the reason I’m reminded of his harrumphing nature. He would have certainly reminded me of all of baseball’s rather sickening complexities, of the bread-and-circuses appeal of all these emotional arguments.

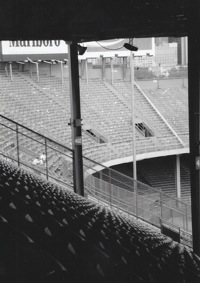

Like that we think the Detroit Tigers, with their high-security, taxpayer-funded pleasure palace, somehow speaks for the city. Same for the Lions. He would remind me that no matter how much we may root on the “small market clubs”, or celebrate that the Cardinals and Rangers are not the Yankees, these teams and their players all share something in common: They’re part of the 1%. Baseball, much as I love it, is part of the problem.

As much as we might admire them, virtually every player is a millionaire or is about to become a millionaire. The team owners are obviously in that rarified air. Oh, they all care about Detroit–you can see it in the interviews, in the fact that owner Mike Ilitch let the big three advertise on his stadium’s wall for free a few seasons ago.

I know the arguments: that the players deserve their piece of that fat pie. True. Sports generates a ton of money. But pardon me if I feel a bit sickened by the fact that these athletes want to leap from the masses who follow them religiously and join the 1% that is sucking so much from America. There’s a ton of good people out there who are millionaires, who make or made tons of money and are demanding social justice. The St. Louis Cardinals and the Texas Rangers are not among those good people. Neither are the Tigers.

When I think of my favorite team, of Justin Verlander, Doug Fister, Brandon Inge, I’m excited, and a bit proud. They’re Detroit Tigers! They beat the fucking Yankees! But I also think of the homeless guys wandering the streets near new Tiger Stadium, often veterans, men who used to work the factories that don’t exist anymore except as fodder for coffee table photographs. A lot of those guys wear beat-up old Tigers’ caps, can probably tell you about the days of Gibson, Trammell, Whitaker, Willie Horton. You can see them when they’re in proximity to a game, doing some small, silly talent like beating a five-gallon paint drum by Woodward Avenue or simply holding a cardboard sign that reads “God Bless”, hoping for some of your coins.

Fact is, no one on the team (or any other baseball team) has anything to say about this crisis that is wrecking suburbs as much as it beats a city already battered from decades of abuse. They play, they win, they lose, they take buses from the stadium to airports that fly them to warmer climes, and from there to gated communities. I wonder if the homeless and downtrodden see buses or SUVs with darkened windows, ferrying those same Tigers far out of town. The fans who can afford to see the games in the stadium drive straight out of town to the affluent suburbs.

I wish to God Dad had been here to add some needed perspective to this postseason. He was planning to move here to Minneapolis in his retirement, and I would certainly have forced him to join me in front of the TV to watch a game or two or three. Christ, them being on Fox would have started him going for the first three innings at least. And he would certainly have looked at this advertisement for the Chrysler 300 with the most outrageous skepticism.

For starters, I imagine that he would have been cynically amused, as I am, that Chrysler chose to sample Bobby “Blue” Bland’s “Ain’t No Love in the Heart of the City”, which seems strangely apropos for an ad about a car from a company that has all but abandoned Michigan. But then I’m reminded that that’s one of Michigan’s great feats: its ability to ignore crushing reality and try and pretend everything’s bright and sunny and humming like a new car.

Most of the neighborhoods in that advertisement are not, of course, in Detroit, and the shots that are in the city limits seem angled to take in a lot of the sky and little of the wrecked homes and empty buildings that make up a great deal of the city. There’s shots of folks on their manicured lawns and beautiful sidewalks. One guy is fixing his bike, and I commend that dude on taking his life into his own hands in perhaps the most dangerous bike city in America.

Then there’s the script. “If you’re gonna build a fuel-efficient car, the first thing you gotta do is make a car that’s worth building. One with character. And conviction…”

Well, there you go. I’ll take Honda’s decision to make cars worth building that are actually built well, because that reflects character and conviction more than the pieces of shit Chrysler continues to roll off the assembly line to this day. But if you use words like “pride” and “character” and “conviction”, Michiganders will line up, open their wallets, drive away a Chrysler or Pontiac and tell you how awful Japanese cars are (which typically support more American jobs than the Big Three), all the while the transmission’s falling out on the Reuther Freeway. Oh, and can you believe that Bob Seeger allowed GM to pay him to use “Like A Rock”? How mighty big of him.

I’m not from Detroit. I lived in Royal Oak for one year, in that hipster enclave a couple miles north of Detroit’s 8 Mile Road border. I’ve always been fascinated by our big city, having grown up on weekends at my Dad’s houses in Bay City and Saginaw. Those cities are smaller versions of Detroit. That industrial blight repeats itself, like a skipping stone, across the eastern side of the state, splashing large in Detroit, then smaller in Flint, Jackson, Lansing, Saginaw, and finally, kerplunk, in Bay City.

As the 70s ground into the 80s, Dad used to get very quiet walking through downtown Saginaw, so dead and empty I’m surprised no enterprising filmmaker thought to shoot a zombie flick there. He remembered it as a vibrant town. I only know it as a place I’d never want to live.

In 2006, when Grandma died, we returned to Saginaw for her funeral, and drove around late at night. We saw the old Roethke florist shop, where Theodore Roethke‘s “My Papa’s Waltz” was inspired, and then by Dad’s old high school, Arthur Hill. When we hit the old Eaton Manufacturing Factory, where he spent 16 years working on steering columns, he was stunned. The giant lot was choked with weeds, the security fence bent and twisted, the doors locked with rusted chain, the windows broken. Graffiti artists hadn’t even seen fit to tag the place. Apparently, even the gangs had abandoned Saginaw.

Dad hated Eaton, couldn’t get out fast enough, but seeing that dead shell where once he put in his thousands of hours of life and labor, playing euchre over lunch, sweating and cursing next to hundreds of other men and women, he was dumbfounded and depressed. “That was harder than I thought,” he said. We drove home in silence.

My friend Brad Zellar shared a heartbreaking music video from Michigan native Mayer Hawthorne, called “A Long Time”, about the city of Detroit. It’s extra sweet and sad because Hawthorn stuck his song onto footage from an old Detroit television program called The New Dance Show. Here it is:

I can only wonder where all those people are today. That thing’s well over twenty years old, and Detroit was so wrecked and ruined then, and yet here these people are dancing like mad. At this time Halloween meant the two to three day Devil’s Night fires, hundreds of homes and businesses burning out of control. At this time half the factories were empty, the other half leaking jobs south, beyond the border to Mexico and beyond. At this time homes became abandoned and then a city block and then whole neighborhoods.

And still they danced. And still they celebrated.

Hawthorne wrote a beautiful song, about Henry Ford and Berry Gordy, how they made the great auto factories and that amazing record label. A time when jobs and music were abundant in the Motor City! And then…

Oh, Henry was the end of the story,

Then everything went wrong

And we’ll return it to its former glory

But it just takes so long…

I’m glad Hawthorne’s writing that Detroit’ll make it, but that it’ll take a long time. That feels honest to me.

When people tell me that the Detroit Tigers are a sign the city’s coming back, a sign that Michigan’s on the rebound, that feels patently dishonest. Justin Verlander sends me into happy fits, as do many of the Tigers. Brandon Inge, who can clobber a home run when the game’s on the line and do nothing the rest of the season, is a favorite. The history of the Tigers moves me, not just as a fan, but as something warm and inviting that speaks to me of family and of the state I grew up in. I’m proud of that.

But this is not a reflection of the true soul of Detroit. The playoffs do not change the fact that the schools are rotten, that the city remains horribly balkanized, divided not only by race but by class. It doesn’t change that baseball players are usually millionaires who might feel a soft spot for the city, but usually don’t live within its borders, and do very little to help their community. Baseball is a glorious illusion I share with other fans… though probably not with other Detroiters. You see, I can afford to go to these games.

This may sound like a clarion call to face every positive utterance about the Motor City with angry skepticism, and in a way it is, but I’m also asking us to celebrate the great things, the people coming into town, the people who have lived there for generations. There’s still three-quarters-of-a-million people in the city, and they’ve been there a long, long time. They’ve run soup kitchens, little barbecue or Coney joints, cleaned up their neighborhoods, stood with hoses ready in front of empty homes on Devil’s Night, ran small businesses that paid taxes and created jobs. These people don’t get advertisements or win pennants or get on the NBC nightly news.

I want Chrysler, Ford, and GM to come back, build factories, get people jobs, real jobs, and not just shitty retail or restaurant work or make more white collar paper shufflers. Manufacturing. Instead of Chrysler shooting a commercial in Detroit for the 300, why not make it Detroit (instead of Canada, China, and Austria)? You do that, and you’ve got suppliers building in Detroit. Restaurants and bars to feed the workers and entertain them.

I hope that’s coming. My Dad would hope that’s coming. That was his great asset: to be cynical and angry and to rage against the machine while also dancing, drinking, and laughing. He wanted life to be real, not to be made up of cheap advertisements and sporting events. He knew that hard work was the secret ingredient of hope. He knew that it meant fighting past the point of exhaustion, fighting, really, until you were dead. Just as the crowd at the end of the video seems to know, when they break into spontaneous chanting, protesting the end of the show: “Don’t. Stop. Now! Don’t. Stop. Now! C’mon! Don’t. Stop. Now!” Now that’s sentiment my Dad would have loved.

It’s gonna take a long time

It’s gonna take it but we’ll make it one day