The Night of the Hunter, 1955. Directed by Charles Laughton, written by James Agee (and an uncredited Laughton.) Starring Billy Chapin, Robert Mitchum, Shelley Winters, Lillian Gish, James Gleason, Evelyn Varden (so I annoying I want to take Preacher’s switchblade to her), Don Beddoe, Peter Graves, and the creepy Sally Jane Bruce.

The Night of the Hunter, 1955. Directed by Charles Laughton, written by James Agee (and an uncredited Laughton.) Starring Billy Chapin, Robert Mitchum, Shelley Winters, Lillian Gish, James Gleason, Evelyn Varden (so I annoying I want to take Preacher’s switchblade to her), Don Beddoe, Peter Graves, and the creepy Sally Jane Bruce.

and,

Davis Grubb’s The Night of the Hunter, published by Harper Brothers, New York, 1953.

We all know of great novels that have been turned into awful movies. But what about those rare moments when a movie is so good that it overshadows a decent source novel? And then there are those times, rarer still, when a great movie’s shadow casts its darkness over a forgotten book that turns out–surprise!–to be superior in every way to the classic film.

Consider the case of the movie The Night of the Hunter. Profoundly bizarre, funny in spots, terrifying in others, referencing silent films and Grimm’s fairy tales and stories from the Holy Bible, Night is a classic flick by any account, and a personal top ten favorite. So imagine my shock when I opened the novel, casually, and began to read the book by long-dead, long-forgotten novelist Davis Grubb. Reading the original made the movie so much more moving. In fact, the book ruined a good many evenings, and got to the point where I literally couldn’t read ten pages without crying. Was screenwriter James Agee moved in the same way? Or director Charles Laughton? Read the book yourself… if you can.

The Night of the Hunter boasts a great plot. Ben Harper (Peter Graves), a young man “just plumb tired of being poor” during this crushing Depression, robs a bank and in the process kills two people. That was his first mistake. His second, and most damaging, is that he takes the $10,000 he’s stolen, stuffs it into his daughter, Pearl’s, doll, and tells both Pearl and his poor son John (Billy Chapin, in an understated and moving performance) to swear to never tell anyone about the money–not even John’s befuddled mother. Then John, suddenly saddled with a burden that will cost many people their lives, watches as the police, the Blue Men, beat his father, handcuff him, and take to him to jail where he’ll die on the gallows.

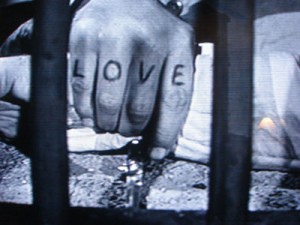

Ben’s secret catches the attention of the Preacher (Robert Mitchum), a switchblade-wielding, tattooed con man and sexual deviant. Preacher was Ben’s cellmate at the Penitentiary. Mitchum’s Preacher wears the words “Love” and “Hate” tattooed on the knuckles of each finger.

He is a man of hate, a man who wants that money. In the past he’s found his riches when God led him to poor widows, whom he married and killed for their money. Now he’s after Ben Harper’s children. And no one, not the foolish Spoon family that helps Willa Harper–Ben’s widow–nor old Uncle Birdie, nor the men and women of Cresap’s Landing, will stop him.

It’s up to the children. And an old woman named Rachel. Perhaps you’ve seen the movie. It’s exciting, fun to watch, and hard to take, mostly because Billy Chapin is so damn good as the beleaguered boy. But the book… oh, Christ, the book.

Davis Grubb’s The Night of the Hunter is about many things. It is about how the Depression ruined a family, that’s one. There’s not time in the movie to develop the family, but in the novel we see that Ben and Willa were a good couple, not too bright, but a simple family struggling to get by. They were real, not this treacly Spielberg bullshit you’d see in movies today, but a family that bickered, laughed, who lived in a house that needed paint and foundation work, who struggled with money, and, after the children were asleep, went to bed themselves a had a good time. A vibrant family.

Their passion makes Ben’s decision to rob a bank, and his execution, heart-wrenching. As is Willa’s floundering in the wake of his death. Though played by Shelley Winters–a great, great actress–the cinematic Willa is nothing more than a silly cow, someone to be pitied. And Ben is nothing but a bank robber.

Like the movie, The Night of the Hunter, the novel, is really the story of John Harper, the boy, whose travails mature him beyond his years. The book, though, is an acute vision of the emotional and spiritual devastation of this young boy in the wake of a crime. In the film, John grows quickly, and the adults are fools. In Grubb’s book, we see the world through this boy’s eyes, a place where yes, his mother is silly, but she’s still his mother, the primary woman of his life, from whom he still seeks comfort and guidance, which he never receives. The police have been warped into Blue Men, who have hurt his father, taken him from the earth even.

The Preacher provokes his instincts–John knows he’s evil–but he is a representative of God, and everyone in town believes Preacher wholeheartedly. When John first meets Preacher at the Spoon family candy store, where his mother now works, his mind is racing:

“Ah, there’s my boy! There’s the little man! Good morning, John.”

“‘Morning.” John tried to smile because they might ask him questions if he didn’t smile.

“Willa, you were truly left a priceless legacy when Brother Harper passed on! These fine, fine younguns!” Willa flushed with pleasure and patted Pearl’s curls more neatly against her shoulders. “Priceless beyond the worth of much fine gold,” Preacher said, “the laughter of these precious little children!”

John stared. The finger named H reached over and chucked him under the chin. John thought: She says he is a man of God. And so God is one of them; God is a blue man.

Look at him, there, trying to force a smile, struggling with his secret, guilty for his feelings, confused as to why the adults are fawning over this man, and, most painfully, clearly missing his father and hungry for an adult to care for him. In the course of this book, we see John go from boy to man, and in every step you just want to cry out and try to reach into the pages to help the poor boy, saddled with this terrible secret. At first he’s a child playing in the dirt to a little man caring for his foolish younger sister (and what child of that age isn’t foolish? or deserves to be foolish?) to a fugitive trying to escape down a river and scrounge for food. His old fear of the dark gives way to a very real fear of this murderer, and we witness the darkness become his friend, and wish that there had been another reason for this. His mother, the Spoons, the townspeople, the police, even his friend Uncle Birdie, who promised him safe haven, will betray him, until he is left to run, to flee, with Pearl in tow. Even God betrays him.

And this is why Rachel is such an important character in both the book and the film (but especially the novel.) So much is made of Mitchum’s Preacher, and for good reason because it is not only an incredible performance but, with James Stewart’s Scotty Ferguson in Vertigo, one of the two great challenging performances in cinema. But he is matched by Lillian Gish’s Rachel.

Without Rachel, The Night of the Hunter would be unwatchable, and definitely unreadable. She gives comfort and security and, perhaps most importantly, spiritual guidance to poor John, but not quickly, and not easily. Rachel is the woman on the river who takes in abandoned children. She has five of them, including a love-struck teen. Rachel herself has been abandoned–her husband is long dead, and her son is a high-falutin’ executive who doesn’t give a hoot about his rube mother. But she doesn’t care. She’ll take care of these kids, she’ll protect them, teach them, make them into kind, loving, strong adults. About this, we have no doubt. Just as we slowly, surely–like John, perhaps–have no doubt she will stand up to Preacher. And so she does.

The Night of the Hunter certainly moved James Agee, who was an emotional wreck anyway. Given the opportunity to adapt the book into a screenplay, it is clear that he struggled to get everything in there, to the tune of 250 pages (about four hours worth of film.) I imagine Agee smoking, drinking, probably fucking his secretary, collapsing exhausted on a dirty bed and then waking, hung over, to wrestle with this script again and again. I see him waking early in spite of a late evening to reread Grubb’s book, scribbling notes in a fury, gulping coffee to offset the booze that he’d sucked down to suppress the ghosts that whispered “You’re failing, Jim, you can’t handle it.” Certainly there were moments when he discovered (as I did) a new sentence or paragraph that made him react with terror that he might have left something out.

Don’t forget, this is the Agee who was given an assignment by Fortune magazine to cover the sharecroppers in the South, and who returned with a 400 page manuscript that wraps around its subject like a ball python around a defenseless rabbit (that’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men if you’re interested.) So it’s no surprise that his screenplay–only recently discovered (the one you can find is the final shooting script, altered by Laughton)–was big and passionate and unfilmable. Kind of like the novel.

Laughton and producer Paul Gregory had had a number of rousing successes on Broadway, and of course, Laughton was a magnificent actor with an Oscar in his back pocket. And he was proud to be working on this book as his inaugural project. Laughton did it well. A noir fable, perfect. Of course you have to leave stuff out, and Laughton and Agee both knew they had to tone down the violence and the suffering and even add some comedy–Agee wanted to add “some Buster Keaton” to the Preacher’s bumbling up the basement steps–and it shows. And it works.

Laughton made the story his own, which is exactly what you should do with any adaptation, great book or no. Only it was a disaster. No one understood the thing–not critics, not audiences. Agee died before it was released. Laughton and Gregory never worked together again. Was Laughton so affected by the book, that he felt personally responsible for it? Was he as moved as I was, as Agee was, and then, making the movie and watching the world recoil, did he feel that he had damaged this beautiful story?

What we know is that he never directed again.

And now this great movie is recognized, but the great book, a more amazing achievement really, hides in its shadow. The book deserves our attention. Like the little children hiding on the raft, Davis Grubb’s The Night of the Hunter hides in the rushes of American pop culture, picked up very casually by the errant souls who love the movie and want more. Read it, and you’ll find yourself in the same fever-dream as Agee, Douglas and Laughton. Despite the anguish, it’s a good place to be.