For over a half a year now, you’ve been reading about my peregrinations around the Twin Cities, plumbing basements and ascending attics in search of trinkets, household goods, books, ties, Life magazines, and most of all, interesting stories.

For over a half a year now, you’ve been reading about my peregrinations around the Twin Cities, plumbing basements and ascending attics in search of trinkets, household goods, books, ties, Life magazines, and most of all, interesting stories.

Every time you wander into a home with the sign out front, every time you read in the newspaper about “fifty years of accumulation”, you have to remember that to get to that point, there’s already been a platoon of dusty souls who’ve worked days to clean, organize, and eventually sell you the possessions of the deceased. Often–heck, always–it’s a huge job.

The Company

In early May, I began to follow the progress of a sale in Minneapolis’ Howe neighborhood, run by Muirfield Associates, one of the Twin Cities best estate sale companies. Muirfield generally works the higher-end sales, typically with fine antiques, in nicer homes. No digger sales, no garage sales. Though that’s usually not my bag, I appreciate their knowledgeable and friendly staff, the fact that they price items well, and that their sales are a model of efficiency and organization. Murifield sales are flat-out fun.

Mark Thompson is the owner and manager, and has been running estate sales since 2002, after more than a decade in the antique business. A former corporate attorney, Mark has the articulate nature of a lawyer–he can speak at length about his business and clientel, spinning some amazing stories but remaining on point throughout the conversation (which I imagine served him well in the courtroom.)

Muirfield holds about twenty-five sales a year, and Mark is very deliberate in his choices. “I turn down three times that many,” he explains. “If the stuff is not interesting in some form or fashion, I’ll say no, regardless of the overall value.”

With a staff of ten part-time people, Mark keeps extremely busy. Despite working behind closed doors every weekday in organizing a future event, he still manages to attend every current sale on the weekend, right from the start. There he is, at 8:00am, handing out numbers to anxious customers. Once the show gets rolling he’s either taking money, racing off to answer a question, or wandering the house to make sure everything’s running smoothly. Even then, he’s already thinking ahead to the next function. And he rarely gets any time off.

Over the years, he’s seen a variety of incredible–and often bizarre–items. When I asked him what was the most expensive item he’d ever sold, I figured it had to be jewelry or an automobile.

“No, it was a duck decoy,” he said. The decoy itself was from famed artist Elmer Cromwell, and Muirfield sold it for $23,000. The buyer restored it and sold it for more than double that. Apparently, hunting and fishing items remain hot properties in the midwest, despite the economy.

The Preparation

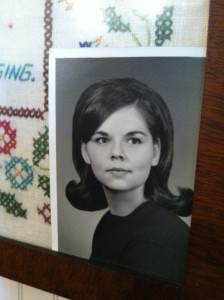

In February of this year, a woman named Nancy Teufert passed away in her home after a long and complicated illness. She was unmarried, and had no children. Her family, consisting of sisters and a brother, contacted Muirfield to handle the estate.

Nancy was an antique dealer, and one of the best in the Twin Cities. Not only that, she was a graphic designer and painter, and very well liked in the her community. Although her home was disheveled, the result of years of neglect after failing to fight off a murderous illness, it was packed full of valuable items, many of which were hidden underneath plain old trash.

Her home wasn’t very large–it was a one-and-a-half story bungalow, the “half-story” essentially an attic, though it could be used as a bedroom. She’d added on a back room that was very much in the style of a New England farmhouse–hardwood floors with wide, rough planks, a big brick fireplace (replete with hooks to hang decorative cast-iron kettles), exposed beams, plain, whitewashed walls. The bedrooms were small; the living room, dining room, and kitchen were small. Because of the size of the place, and the volume of material, the sale would be divided over two weekends. This meant removing some items and hauling them upstairs to the attic, and organizing what remained.

The first step was clearing away the junk from the treasure. It’s in the best interest of the client to contact an estate sale company right away, and allow the experts to determine what’s what. Mark remembered an older sale, years ago, where one family happily told him that they’d already cleared away a ton of junk into a dumpster in front of the house. “They told me they only threw out the old paperwork,” Mark said. Alarmed, he and one of his partners leapt into the dumpster, dug around and found stacks of autographs… including a photo of Marilyn Monroe that sold upwards of two grand.

Nancy’s house proved to be challenging. “Every cupboard and drawer was filled with stuff,” Mark said. The Muirfield team went to work almost immediately after being hired. Knowing that Ms. Teufert was an antiques expert, he and his crew were extra careful not to throw away any valuables.

Nancy’s house proved to be challenging. “Every cupboard and drawer was filled with stuff,” Mark said. The Muirfield team went to work almost immediately after being hired. Knowing that Ms. Teufert was an antiques expert, he and his crew were extra careful not to throw away any valuables.

But even an antique collector owns material that is nothing more than garbage. They filled a dumpster, and by the time I came in (see photo, left), when the place was still almost impossible to get through, even though Mark and his team had already spent 60 plus hours working on the sale.

Much of this was spent cleaning. Years of accumulation coupled with a person barely able to care for themselves in the end means that items get dusty, tacky. “We spent ten hours cleaning just cleaning the items in the kitchen,” Mark said. All of the dishes had to be scrubbed, and every table, shelf, picture frame, Christmas ornament, and basket (among many, many items) had to be dusted. By the time I arrived, the place was disheveled, but spotless for the most part.

After separating the junk from the not-junk, and cleaning, then there’s the physical organization. Muirfield’s sales are easy to maneuver in part because they spend forever making sure that similar items go into one room, much like a store… that is, if all of one type of item will all fit into one room. Nancy had baskets, silverware, tons of linens and was known for her collection of Christmas items. Despite being an antique dealer for some time, in later years she was just a collector, and didn’t organize. For instance, one room was dedicated to holiday items, so when they found Santa Claus baubles in the bedroom or basement, they were hauled to the back office, to be staged for the sale. And don’t forget, the sale was so big as to be held over two weekends–so some material was dragged upstairs to the attic, for the following weekend.

After separating the junk from the not-junk, and cleaning, then there’s the physical organization. Muirfield’s sales are easy to maneuver in part because they spend forever making sure that similar items go into one room, much like a store… that is, if all of one type of item will all fit into one room. Nancy had baskets, silverware, tons of linens and was known for her collection of Christmas items. Despite being an antique dealer for some time, in later years she was just a collector, and didn’t organize. For instance, one room was dedicated to holiday items, so when they found Santa Claus baubles in the bedroom or basement, they were hauled to the back office, to be staged for the sale. And don’t forget, the sale was so big as to be held over two weekends–so some material was dragged upstairs to the attic, for the following weekend.

Then there’s the research. Although Mark and his staff, including longtime employee John, are well versed in the various nuances of pricing antiques, they don’t know it all off the top of their heads–there’s still a ton of online digging to be done. Consider the old grandfather clock in the living room. “Experience tells us to look inside,” John said, walking me over to a gorgeous clock in the front room, and gingerly opening the door to the weights and pendulum. There, on the inside of the door and in a slightly primitive hand, were a set of initials from long ago. Are these the initials of someone who owned it long ago? The clockmaker? And perhaps most importantly: does this add to the value of the clock?

Then there’s the research. Although Mark and his staff, including longtime employee John, are well versed in the various nuances of pricing antiques, they don’t know it all off the top of their heads–there’s still a ton of online digging to be done. Consider the old grandfather clock in the living room. “Experience tells us to look inside,” John said, walking me over to a gorgeous clock in the front room, and gingerly opening the door to the weights and pendulum. There, on the inside of the door and in a slightly primitive hand, were a set of initials from long ago. Are these the initials of someone who owned it long ago? The clockmaker? And perhaps most importantly: does this add to the value of the clock?

Some items were plain baffling: for instance, do you know what this weird bullet-looking thing is to the left? Turns out it’s a “knitting bullet”–it holds knitting needles and yarn, which is fed from a little hole near the top (right.) How much do you charge for such a thing ($75 as it turns out.)

Some items were plain baffling: for instance, do you know what this weird bullet-looking thing is to the left? Turns out it’s a “knitting bullet”–it holds knitting needles and yarn, which is fed from a little hole near the top (right.) How much do you charge for such a thing ($75 as it turns out.)

When I was taken aback at a copper kettle selling upwards of $400, Mark explained that it was the handiwork of one G. Tryon, of Philadelphia. Mr. Tryon was prominent coppersmith in the 1800s. “This won’t be discounted, either,” Mark said, referring to the custom of selling items at 30-50% off on the last day. Turns out that he knows of an auctioneer in Pennsylvania who would get even more money there, as Keystone state citizens are mad for antiques from their own backyard. They were going to get that $400. “I knew about this one,” he said, but noted that sometimes it takes him over two hours of research to price an item. He shrugged. “It’s fun.”

When I was taken aback at a copper kettle selling upwards of $400, Mark explained that it was the handiwork of one G. Tryon, of Philadelphia. Mr. Tryon was prominent coppersmith in the 1800s. “This won’t be discounted, either,” Mark said, referring to the custom of selling items at 30-50% off on the last day. Turns out that he knows of an auctioneer in Pennsylvania who would get even more money there, as Keystone state citizens are mad for antiques from their own backyard. They were going to get that $400. “I knew about this one,” he said, but noted that sometimes it takes him over two hours of research to price an item. He shrugged. “It’s fun.”

Sometimes there are wild cards, like the many paintings in the house, most of which were by Nancy’s own hand. Mark priced a couple of nice ones at $125, because many of her friends admired her work, and might be intrigued to own some for themselves.

After a few weeks, the place began to breathe a bit. “People need to be able to stand back and really look at that grandfather clock,” Mark noted. By now almost every item had a paper price tag which was attached by string. This takes a lot more time than just slapping a sticker on the thing, but I for one appreciate the effort. There’s nothing more irritating than peeling a sticker off a valuable paper item, only to watch the glue rip part of the cover off.

The Sitter

The Wednesday afternoon before the sale, which was to be held on Saturday (there was a Friday pre-sale of garage and garden material, but the house would be off limits), Mark had finished leading me around the house, and explaining their progress when he noticed someone sitting on the small front porch by the side door. This was Carol, an antique dealer and a personal friend of Nancy Teufert’s. “Are you showing her something?” I asked.

“No,” Mark laughed. “She’s already in line.”

Here we have one of the stranger aspects of the estate sale world: sitters. If you read the advertisements for sales, you will almost always see a line that reads “Numbers at–” and then a time, usually 8:00. The company running the sale has a stack of playing cards, or notecards with numbers written on them. Because popular sales are busy right at the get-go, and the house in question only holds so many people, they have to restrict the crowds, for safety and just to keep it from being a madhouse.

But when a sale has a certain special appeal, that brings out the sitters. Carol would only there for a short time–later she would have a man named Andy come and sit and wait through the night. In this case, Carol would relieve Andy during the day, but there are many occasions, such as this, when the sitter’s there for days.

Naturally, I was stunned at this development. I mean, we’re talking over sixty hours of waiting. I made it a point to stop by the house that evening to talk with Andy, and see what the sitter did in all this time.

Andy looked to be in his thirties, and he was loafing on the porch reading S. E. Hinton’s The Outsiders. He was a quiet man, who does a number of odd jobs for various antique dealers. In fact, he’d worked for Muirfield before.

“It’s easy money but it’s not easy money,” he said, and I could see why–one one hand you’re just waiting. On the other hand, you’re just waiting. But he seemed nonplussed by the prospect of three nights camped out in front a house. He pointed to Carol’s SUV, his home for the next three evenings. Mark kindly gave Andy a key to the house, because there were furious thunderstorms predicted, maybe even a tornado. When I said that was nice of Mark, Andy nodded. “Well, he doesn’t want me to blow away.” To keep the neighbors comfortable, he’d made it a point to introduce himself to people he saw strolling by, so that they didn’t wonder about the dude sleeping in his car in their neighborhood.

Andy explained that he had stocked the car with snacks, books, blankets, sheets, and an “old pillow.” In the winter, they have more blankets and run their vehicles about every fifteen minutes to keep from freezing. Sitters don’t drink a lot of liquids and try and avoid salty snacks, so they don’t have to use the restroom (though he said he had an empty bottle–I wondered if he warned the neighbors about that.) “We relax the rules a bit for women,” he said, stating matter-of-factly that a female sitter can take 15 minutes to run to a gas station bathroom. “But that doesn’t mean they get to leave to eat or anything,” Andy said, illustrating this with a tale of a pair of women who asked him and other sitters if they’d mind allowing them a 30 minute break for dinner. “Yes, we did mind,” he said.

“The rules” in this case turn out to be a “pre-numbering” system. Other sitters (who in this case arrived on Friday), would take a number from a plastic sleeve Andy had attached to the window of Carol’s truck. In other words, if you arrived early enough, you had to take a number to get in the line to take a number from Mark, in order to be in line for the sale.

When I asked Mark about this, he said it was standard procedure. This seemed strange to me. For instance, if I’d read about a sale featuring piles of beautiful old Mad Magazines, I might get up at 6:00am to get in line for numbers at 8. If someone told me of a numbering system separate from the people who were actually running the sale, I’d be pissed–it’s not as though they’re actually standing in line for all this time. But Mark said arguments like that were rare, and when it does happen, “usually we just negotiate,” he said. “It always works out.”

The Sale

On Saturday, I arrived around 6:45. There were pickup trucks and SUVs and a banana yellow van parked in the street, one from as far away as Florida. A huge conversion van was right in front, decked out with a Coleman lantern, stacks of books and DVDs, a cooler, and a twin bed, was parked on the street out front. Just past dawn, the sound of the birds was brilliant. People were gathered in clusters, some drinking coffee, and everyone was very congenial–they’d known Nancy, and knew one another. At that moment there wasn’t the edge of competitiveness I’d expected.

On Saturday, I arrived around 6:45. There were pickup trucks and SUVs and a banana yellow van parked in the street, one from as far away as Florida. A huge conversion van was right in front, decked out with a Coleman lantern, stacks of books and DVDs, a cooler, and a twin bed, was parked on the street out front. Just past dawn, the sound of the birds was brilliant. People were gathered in clusters, some drinking coffee, and everyone was very congenial–they’d known Nancy, and knew one another. At that moment there wasn’t the edge of competitiveness I’d expected.

I looked at the window of Andy’s car and saw that the pre-number total had reached 35.

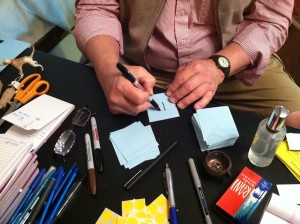

Mark arrived around 7:00, having just finished driving around and leaving Muirfield signs on busy streetcorners instructing customers to Nancy’s house. We went inside as he got the last details ready. His employees began to show up: Mark’s wife Susan, John, and a host of others, who’d either worked for Mark over the years or, in one case, had been friends of the family and loved working these “adventures”. There was last-minute cleaning to attend to, money to be counted, people assigned to work certain rooms during the sale, receipts to be readied. Then Mark sat down and began to write the numbers on little cards.

At 8:00 he strolled out to the front gate and the people crushed to the front. Mark said, “How was the slumber party?” Then he proceeded to hand out the numbers and explain the general rules, which included the fact that there was no “calling”–the buyer couldn’t just race through the house and shout “I want that!” and expect the Muirfield associate to jump and slap a SOLD tag on the thing.

After handing out numbers (and leaving the remainders in a pile on the porch), Mark retreated back inside, the doors were closed until the sale began at nine, and people went right back to chatting. The crowd was fairly calm, but Mark said that sometimes you’ll see people auction off their numbers. “Once I heard a #42 offer $250 to a #2.”

“I’ve waited three days before,” John said as he swept the floor. He shook his head. “Wouldn’t do it again.”

About a quarter to nine, we ran into trouble. “My #1 is missing,” Mark said. Carol had called him to say that she’d gotten lost on her way from Wisconsin. Suddenly she was bounding south on 35W. Andy, her sitter, didn’t have the money or any idea of what she wanted–he was just a warm body holding a spot in line. Fortunately, with five minutes to spare, Carol arrived, flustered but happy she’d made it.

“Not many people can get this kind of adrenaline rush from getting lost,” she said, out of breath. “Maybe a sea captain, but not many others.”

At 9:00, with the Muirfield folks situated, pens in hand, pads in hand, aprons on, and ready, Mark opened the door.

It was a bedlam. Carol ran in first and slapped a SOLD tag on a painting behind the cashier. Dealers have pads of post-it notes with their name on them, and the single important word: SOLD. The first twenty people raced into the New England room with all the baskets and silver, pushing through the kitchen into the bedroom with the linens, into the office with the Christmas items, or into the living room with the grandfather clock and the tiger maple furniture. There was shouting–not unpleasant, but certainly loud–and at one point someone grabbed me and said, “Sir, I want that rug you’re standing on. The name’s Drake…” So I made a sale myself.

Despite all their efforts, there were still a few items that had slipped through the cracks. Some of the smaller ornamental fake fruit hadn’t been priced, and an iron piece had a tag, but nothing written on it. You could hear people pondering certain items–the knitting bullet caused a stir–and you could see dealers eyeing one another as well.

John nodded at those folks. “Seeing who was in line, you know what’s going to sell,” John said quietly, between writing up slips. “Sometimes, you get people buying defensively, buying out of fear someone else will get it, even if the item’s not something they really wanted.”

The line was gone by 9:35; by 9:45 there was a line to pay for items; by 10 there was another line out the door, as late arrivals began to show (that would have been me if I wasn’t writing about this one.) The gent who wanted the rug wanted it right then–so, with 15 people in the room and a dining room table resting on it, the Muirfield people managed to clear everyone away, roll the dusty thing up, and haul it, twisted and cumbersome, out of the room and into the customer’s van.

During the sale, someone actually called Mark on the phone and asked, “What do you have there?” He just rolled his eyes. “I love it when we get those. And we get them a lot.” Carol, the one who’d arrived on Wednesday, was ecstatic–she got her prize, an old silhouette (right.) When I asked her if it was worth all the money and effort, she nodded enthusiastically.

During the sale, someone actually called Mark on the phone and asked, “What do you have there?” He just rolled his eyes. “I love it when we get those. And we get them a lot.” Carol, the one who’d arrived on Wednesday, was ecstatic–she got her prize, an old silhouette (right.) When I asked her if it was worth all the money and effort, she nodded enthusiastically.

I remained at the sale until around 11:00, as by then it had definitely slowed down to a steady trickle of people, some with merchandise and some without.

The sale would go on to Sunday, when most items were discounted, and then Mark and Co. would begin working on the “backside”–the removal of what didn’t sell. The family had already sold the place to a flipper, who was patiently allowing Muirfield the time for both sales and removal of what didn’t go. On the backside, Mark had considerable tools at his disposal–he always helps help his clients get rid of what remains, either by donating them to Goodwill or the Salvation Army (for a tax deduction), selling them at auction, or just getting the stuff hauled away to the dump.

The sale would go on to Sunday, when most items were discounted, and then Mark and Co. would begin working on the “backside”–the removal of what didn’t sell. The family had already sold the place to a flipper, who was patiently allowing Muirfield the time for both sales and removal of what didn’t go. On the backside, Mark had considerable tools at his disposal–he always helps help his clients get rid of what remains, either by donating them to Goodwill or the Salvation Army (for a tax deduction), selling them at auction, or just getting the stuff hauled away to the dump.

Surprisingly, the grandfather clock didn’t sell. Since there would be yet another sale featuring Nancy’s possessions, Mark was confident it would go later on. There were a number of her paintings, some upholstered furniture (“the market has completely died on furniture”), and other small items.

But the emptiness was palpable, and a little bit melancholy. I like Mark and his staff, and came to respect them even more after watching them in action. This isn’t meant as an advertisement–if you like estate sales, you really should hit all of them, and if you’re looking for a company to help you handle this situation in a time of grief, then I hope you’re not turning here for guidance. But watching the Muirfield crew at work, I was struck by the fact that their labors are both interesting and noble. They help the family, often grieving. But even if the relatives didn’t know the person, even if they barely knew the deceased, it is still a comfort and a convenience to have someone sort through the often intimidating detritus that a person can amass in a lifetime.

After all, this Nancy Teufert spent a her years accumulating merchandise that she herself used to sell, and she had a great eye. Her ability to judge an item not only as valuable, but as beautiful, was palpable. Her family and friends respected that–and it appears she had a lot of friends. Nancy’s online obituary is terse, but judging from the kind things I overheard at the sale, I’m guessing she was a kind person, well liked in her community, and highly thought of as a professonal. Buying and selling antiques was a career, just as it was a passion. It gave her life meaning. And just as a great composer would hope that a respected peer would write a requiem that served and heightened the occasion, so, too, did Nancy deserve to have a host of good people assessing and selling the antiques that she worked diligently to acquire. From my two weeks following Muirfield, it seems to me that Nancy was given the good treatment that she deserved.