I was ten years old when I first saw Citizen Kane. My father hauled my brother and me to the enormous Temple Theatre in downtown Saginaw, Michigan, and with a crowd of maybe two dozen, we noticed that Kane was more than just a chapter of film history; it was hilarious and melancholy and eminently bizarre. Like the eponymous boy in The Little Prince (which Welles at one point adapted into an unfilmed screenplay), Charles Foster Kane is less William Randolph Hearst and so much more the young Orson, bouncing from experience to experience in his fruitless quest for true love. Here was a curious and melancholy figure, trying desperately to hold on to his childhood as he grew older. Just like the rest of us. Or so I thought.

I was ten years old when I first saw Citizen Kane. My father hauled my brother and me to the enormous Temple Theatre in downtown Saginaw, Michigan, and with a crowd of maybe two dozen, we noticed that Kane was more than just a chapter of film history; it was hilarious and melancholy and eminently bizarre. Like the eponymous boy in The Little Prince (which Welles at one point adapted into an unfilmed screenplay), Charles Foster Kane is less William Randolph Hearst and so much more the young Orson, bouncing from experience to experience in his fruitless quest for true love. Here was a curious and melancholy figure, trying desperately to hold on to his childhood as he grew older. Just like the rest of us. Or so I thought.

Reading about Orson Welles in the hopes of understanding his character (or his movies) is akin to dropping into a deep and unmapped cave. For someone who made only twelve full-length features (one remains unreleased due to myriad legal problems, and there are many others he may or may not have directed), Welles has had a tremendous amount scribbled about him.

On the whole, the assessments about the man and his career are notably contradictory. Pauline Kael staked part of her considerable reputation on devaluing Welles’ contributions to his masterwork in her “Raising Kane,” a thirty-five-year-old New Yorker essay that is hotly debated to this day. Another eminent writer on film, David Thomson, went bonkers in Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles, analyzing much of Welles’ life and making an unfounded accusation that he raped an actress in one of his films. Director and friend Peter Bogdanovich interviewed Welles, who spun so many tales that the resulting book reads like a cineaste’s Thousand and One Nights, with most of the facts twisted to suit the moment. Followers have held up the man as a genius, while detractors slam him for failing to live up to the promise of Kane.

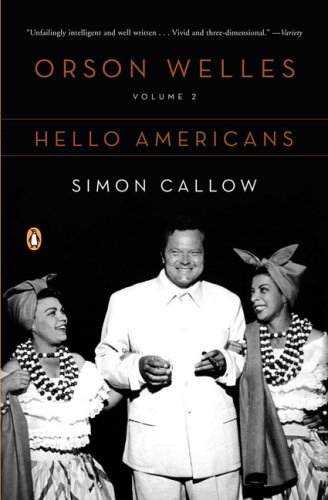

Now, adding to the dozens of volumes on Welles and his work, there’s Orson Welles: Hello Americans. It’s the second volume of a three-part biography by Simon Callow, probably best known as an actor (his was the funeral in Four Weddings and a Funeral). Considering that this labor of love was originally proposed as two volumes, it could very likely stretch to four should the excesses of Welles’ later years begin to overwhelm his biographer.

Hello Americans is a strange but effective book, encompassing only seven of the director’s seventy years, albeit perhaps the most thoroughly documented ones. It opens in 1941, as Welles basks in the critical afterglow of Citizen Kane, with the cinematic world his proverbial oyster. He had a sympathetic studio head in RKO’s George J. Schaefer, America had recently plunged into World War II, the press was still very much awed by the boy wonder, and Welles himself was bursting with ideas. As Callow writes, “Welles was an early sufferer from the condition … described as projectitis. His fertility in engendering ideas was astonishing.”

In the short span between December 1941 and February of the following year, Welles seemed like a kid with an extreme case of Attention Deficit Disorder. (He actually took amphetamines to keep his weight down.) He met Rita Hayworth, whom he would eventually marry; worked on a short film about bullfighting in Mexico called Bonito the Bull; and labored continuously on his radio programs and those of his contemporaries—including Norman Corwin’s We Hold These Truths, rightly considered one of the finest radio shows in history. All the while Welles was toying with the notion of making The Life of Christ, bringing Mein Kampf to the screen, and selling a germ of an idea that would eventually become Chaplin’s overpraised Monsieur Verdoux. Finally, he settled on making not one but three films to follow up his freshman triumph—the tragic Magnificent Ambersons, the relatively unseen thriller Journey into Fear, and, most ambitiously, It’s All True.

The Magnificent Ambersons is often referred to as Welles’ most butchered film, and the best example, for his supporters, of how the studio bosses quickly lost their faith in the wunderkind when his films strove for brilliance over commercial success. (By early 1942 it was evident that Kane, despite the glowing reviews, was going to lose money.) To his detractors, Ambersons provides abundant evidence of the genius-as-spoiled-brat, for with it—and many of his later films—he would prove uninterested in finishing the product or working within the system.

Callow’s scene-by-scene critique brilliantly takes the reader through this relatively unseen picture, which tells the story of the wealthy and out-of-touch Amberson clan at the turn of the last century as their fortunes declined with the rise of the automobile. What remains of Ambersons boasts some of Welles’ most assured direction and shows his strong hand with his actors while also offering a foray into the sentimental mind of its creator. Welles made Ambersons, which he narrated but did not appear in, while simultaneously starring in and clandestinely directing (with Norman Foster) the forgotten thriller Journey into Fear. Here, Callow shows Welles as a man with far too many plates spinning in the air. With insufficient time to helm both films, Welles gave Foster extensive notes—and full credit—for directing, something he was hitherto unwilling to do. Shooting on lots as opposed to location, Welles and many of the loyal Mercury actors were shuttled between the two pictures, shooting one after another and racing between sets. Joseph Cotten, who appeared in both films, was even pressed into writing Journey’s screenplay when Welles became too busy.

In early February, Welles finished work on Journey, concluded principal photography on Ambersons, then fled, two days later, to Brazil. While juggling both Journey and Ambersons, Welles had been pegged to film the famous carnival in Rio de Janeiro. Given that his flat feet and bad back had kept him from putting on fatigues, it was Welles’ attempt to do his part for the war effort.

The footage he shot in Rio would become the basis for It’s All True, his fourth feature. Despite some vague directives from the federal government about strengthening “pan-American” unity during wartime, no one, least of all Welles, knew quite what this film would be about. But that doesn’t mean the director was apprehensive. To the contrary, he was thrilled at the prospect and managed to convince officials from the studio, the government, and his own stable of Mercury actors to join him in South America for a project that he himself could barely articulate. All he knew was that it would be fabulous.

This was the first of Welles’ many glaring mistakes. Having finished principal work on both Ambersons and Journey, he left the fate of the former picture in the hands of the pedantic editor, Robert Wise (despite the passionate entreaties of his allies at RKO). Preview audiences loathed it, so Wise, with RKO’s support, mangled the film, cutting it from 148 minutes to just 88. The studio stuck it on the tail end of a double bill, and in a matter of weeks the film vanished, losing the studio’s shirt in the process.

Working in Brazil, Welles was at first oblivious to all this. Stranger still, once he was clued in to the problems back in Hollywood, he ignored pleas to return to the states to try and save his film from RKO’s money-driven suits. Down south, things went from triumphant to disastrous. Initially greeted as a hero, Welles shot miles of film, often with his camera pointed at the wrong people (the Brazilian government did not want the world to see its poor, its lascivious, and especially its darker-skinned citizens). After months of often scatterbrained work (Welles still hadn’t provided RKO with an acceptable plot outline for It’s All True), the studio cut off his financing. His reputation took a beating, and in shooting the “Four Men on a Raft” sequence, one of the four original sailors drowned while recreating a scene.

It’s All True ended up essentially unmade. Journey, released a year after Ambersons, failed miserably. Welles would never again taste the freedom that he’d enjoyed with Citizen Kane. The Magnificent Ambersons and Journey into Fear are unavailable on DVD in the United States; what remained of the miles of It’s All True footage was cobbled together in a virtually unseen documentary of the same name in 1993.

This episode, perhaps little more than a year in Welles’ life, takes up about a third of Hello Americans but offers the most telling clues about the character of this amazing, and amazingly aggravating, artist. After his failed cinematic hat trick, Welles temporarily abandoned filmmaking, throwing himself into politics. He worked tirelessly for Roosevelt, considered a run for president, wrote a daily newspaper column that flopped, and became embroiled in a hugely controversial moment in the Civil Rights movement, working to hunt down a Southern sheriff.

Then, in 1946, he staged the ambitious musical Around the World in Eighty Days (another flop), among other pursuits too numerous to summarize. He also got back into the director’s chair that year, overseeing a mediocre thriller, The Stranger, followed by the classics The Lady from Shanghai and Macbeth.

Callow’s biography leaves off as Welles flees to Europe, both to avoid the taxman and to find comfort in the greater appreciation for his work on that continent. Once again, he abandoned a movie (Macbeth) in postproduction and remained a wayward traveler to the end of his days.

Critics of Hello Americans have been as divided as those critics of Welles himself. Some accuse Callow of hagiography, others suggest he’s nearly libeling the man’s reputation. But I found Hello Americans to be a surprisingly evenhanded account of an often infuriating artist. In fact, it’s Callow’s mastery of acting that makes his analysis of Welles’ films required reading for anyone interested in why movies succeed or fail. He tries to come to grips with the legend, sorting through enough material to fill the great warehouses of Xanadu.

What results is like a kaleidoscope pointed at a moving picture; every reader of Hello Americans will come away with a different image of the fractured Orson Welles. Which is just as it should be. Reading the many Welles biographies and the stories he himself spun, one wonders if their subject was purposely trying to keep his legend, as opposed to his reality, alive. He always wanted us to return to his movies and forget about him.

Callow’s work on the third installment—Welles in his last years, from 1948 until his death in 1985—should prove almost as quixotic as the man whose life he is writing, for it will take him from the land of strict documentation into the shadowy realm of the unknown. Whereas Callow could previously avail himself of the Lilly Library at the University of Indiana—a storehouse of Welles’ material, from letters and speeches to manuscripts, photographs, and films—he will now have to hunt down individuals and innumerable loose ends; Welles’ own record is notoriously dubious. It’s hard not to wonder if we wouldn’t be better served by heeding filmmaker Ernest R. Dickerson’s loving analysis of Citizen Kane: “One word can’t explain a man’s life. But the final two words in this film can: ‘No Trespassing.’”

This article originally appeared in The Rake magazine.